It’s certainly a popular argument that Wes Anderson’s style has overshadowed the actual merits of his films. There have been times when I’ve leaned towards agreeing with that, especially as the mannered nature of his work has became more and more focused.

On the other hand, Anderson’s animated films (Fantastic Mr. Fox, Isle of Dogs) have always made perfect sense to me. In stop-motion, he and his crew are literally playing with puppets and miniatures, so we don’t have to worry about what the intent of that artifice is — it’s just built into the medium. While I appreciate the design of films like Grand Budapest Hotel and The French Dispatch just as much, I’m usually more on the fence about the purpose of the visual and tonal rigidity within the context of live-action.

Regardless of how you evaluate Anderson’s individual films, though, I think it’s a net positive for cinema to have directors with clear artistic interests, even if it doesn’t connect for everyone every time. His films are fun, funny, interesting, and look amazing — not a ton to complain about.

It wasn’t until I watched Asteroid City that Anderson’s style began to reveal a deeper layer of purpose, at least in my own understanding. I think there’s a good reason for the laying out of sets and props in his frames like he’s getting ready to pack them up to go on a hiking trip. Check out this video, which explains a principle used in the studio of conceptual artist Tom Sachs.

The point of knolling is that it allows you to see all of the materials and tools at your disposal. When Anderson populates his scenes with deliberately placed objects, he is not just creating background texture to fill out the frame. He wants us to SEE everything.

Sachs’ and Anderson’s work seem deeply connected: both have an intense interest in the meaning of objects and physical spaces. For Sachs, (and for Anderson in Asteroid City) it’s particularly those objects that are uniquely embedded in the American experience.

If the material worlds that your characters inhabit matter to you deeply, why would you NOT want to film them this way?

This became clear to me during Asteroid City for a reason: I’m just as interested in the stuff of this particular effort as Wes is. The titular fictional town is the perfect storm of Christine Gerardi aesthetic obsessions: mid-century industrial design and architecture, the American Southwest, and space-related technology.

An extended shot early in the runtime that introduces the town is has got to be most impressive example of knolling in motion ever created. It shows us everything — the diner with its menu items painted on the front, the crater accessible by a gated chain-link runway, the one-pump filling station, the auto motel. The half-built highway overpass to nowhere. The space research laboratory with telescope. The lineup of vending machines where the American essentials can be obtained: coffee, candy, cocktails, ammunition, real estate. Everything will serve a narrative or symbolic purpose in the story that is to follow. It’s important for us to see it all.

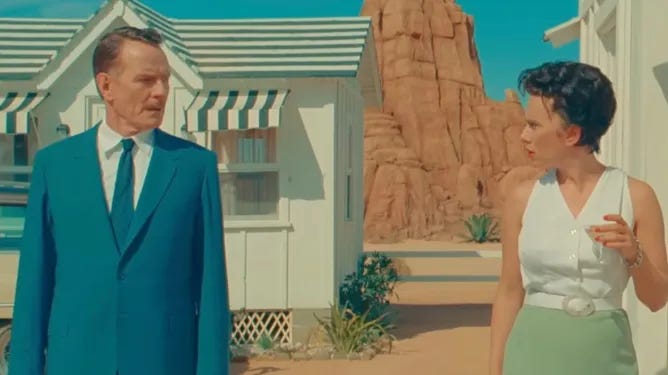

What’s unique and crucial to Asteroid City is its framing device. It presents a twilight-zone style television show (hosted by Brian Cranston) about the production of a play, Asteroid City. Everything in widescreen color is the play, which is interspersed with black and white vignettes of its behind the scenes dramas. For most (read: normal) directorial styles, this might get confusing, but here it’s actually really easy to follow. Anderson lays out the mechanism clearly and succinctly, like all those tools laid out on the workbench.

In Asteroid City, nuclear test explosions shake the chairs in the diner regularly. The play’s action is set during the annual convention of the Junior Stargazers, where Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman), an off-duty war photographer, is chaperoning his teenage son Woodrow (Jake Ryan) to the event with his three young daughters in tow. Augie’s wife, the kids’ mother, has just died. Everything that happens to and around Augie feels like a portent of doom.

He meets fellow parent Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johannson), a Hollywood actress in between film roles, who has brought her daughter to the event. She has a black eye, which is fake. She explains that the character she’s preparing to play doesn’t literally have a black eye, just psychologically.

Then doom personified shows up, in the form of a brief visit from an extraterrestrial. Despite all of the ribbing that Anderson takes for portraying everything in mundane deadpan, he knows how to create moments of genuine wonder. The alien’s reveal felt as weighty and astonishing to me as it did for the characters.

The governmental reaction to this world-altering incursion is as all-American as the hot dogs and chili served at the Stargazers’ dinner: the town is quarantined, the military alerted, and the witnesses interrogated.

The existential questions posed by the extraterrestrial’s appearance send the visitors to Asteroid City into various types of tailspins. Some are inspired to create art about what they’ve experienced, including one of the funniest original songs I have ever heard in a movie.

As the characters lose their grip in the text of the play, the lines of the movie’s framing device begin to get slippery as well.

Brian Cranston suddenly appears two layers out of place. Performers break character when their scene partners make unexpected acting choices. The actor portraying Augie, Jones Hall, walks off the set in a confused panic about the play’s meaning, and what his performance means within the context of it.

This is where Asteroid City becomes an entirely different type of Wes Anderson movie: as he breaks down the boundaries between the meta-layers of the film, Anderson is also breaking the barriers that he’s established over his entire career with his audience. If his prior films presented intricate dioramas without comment, here Wes invites us to stand with him over his art project and asks us what we think of it. His style has always been loud, but this feels like the first time we’re hearing Anderson’s voice, in the form of Jones Hall’s desperate plea for guidance:

“Am I doing it right?”

That feels like a really important question right now. On top of the world kind of falling apart generally, our mechanisms for freely creating meaningful art are in disarray. The margins of error under the thumb of profit demands are increasingly slim: even for an established director like Anderson, failure is seeming like less and less of an option.

Asteroid City pipes this anxiety into our ears during the opening credits:

Last train to San Fernando / Last train to San Fernando

If you miss this one / You might not get another one

A lot of people do NOT think that Wes doing it right, or worse, that what he’s doing is trivial and easy to replicate (you’ve seen the tiktoks and AI-generated parodies). So what do you do as an artist when the mushroom clouds (symbolic and/or literal) are getting closer and closer? Did you actually make anything of value in the first place if the entire endeavor feels like it’s running out of steam?

The director of the play, Schubert Green (Adrien Brody) doesn’t have a clear idea either. He advises the actor:

“Keep telling the story”

In the play, Augie and Midge are both professional artists: they connect over the fact that their lives revolve around the “next thing they plan on doing”. This doesn’t leave a lot of space for reflection on why they are doing it, or what the long term impact will actually be. One long-term impact is their children — they’ve both raised high-achieving creatives. At the end of the play, Woodrow shows his grandfather his plan for next year’s Junior Stargazer science project. He’s already in “next thing I plan on doing” mode.

When you’re more interested in your work than anything else, your work inevitably becomes a part of you in a deeper way than it does for a normal person. Midge comments that she doesn’t know if she’s actually experienced every emotion that she pours into her acting roles. For Jones Hall, the role of Augie is encroaching on his psyche, causing him to actually feel the grief that he’s portraying on the set of Asteroid City.

Our art makes us as much as we make it. We don’t know how it’s going to shape us at the outset. That’s part of why generative AI is so horribly useless to humanity. Even if it could in theory make something we’d like to consume, It doesn’t do for us what art does for us because we aren’t making it. It can’t.

I’ve always been a bit confused when people speak glowingly of the performances in Wes Anderson’s movies. The actors, kind of famously, are not doing a ton in terms of emoting. To be fair, I think I’m having selective memory and plenty of actors in these films are conveying emotions, but Jason Schwartzman’s performance in Asteroid City really affected me, and I’ve been trying to understand why.

It could be that this observation is colored by my own personality, but the hardest conversations I’ve ever had in my life probably came pretty close to resembling Wes Anderson dialogues. Sometimes when we’re hurting so bad, all we can manage do is flatly state the facts of what’s happening to us.

“We’re in grief”

It’s possible that the mannered restraint that Anderson uses in both the writing and the performance actually edges closer to reality than film conventions have trained us to think. The loudest Augie ever gets is when he’s instructed to yell out a line in a screenplay while helping Midge rehearse — performing what a strong emotion is supposed to sound like. When the messiness of the emotions do come up, words often don’t. Augie’s father-in-law (Tom Hanks), reeling from the death of his child, can only register his frustration at Augie with “RRRRRRRG”.

I’m manifesting it now — Jason Schwartzman for Best Actor. Am I crazy?

Or maybe I’m the real Wes Anderson character. Much to think about!