At last, The Blog is back! New subscribers, welcome. Old subscribers, sorry!

If you’ve ever driven through the California’s San Joaquin Valley, it’s easy to guess why Modesto native George Lucas imagined his hero’s home to be a farm on the edge of the galaxy. If you grew up there, you’ve known it all along: The Valley is Tatooine.

Yes, I call it The Valley. Everyone is allowed to refer to their valley of origin as The Valley, apologies to Paul Thomas Anderson and the Haim sisters.

When I was a very small child, I was under the impression that whenever my family traveled from Fresno (or Clovis to be really specific) to Los Angeles or San Francisco, we were going to a different planet, although I was confused as to how that transition was so smoothly accomplished by car. This was in concept a reasonable thing for me to think: that’s what Luke Skywalker had to do to get to anyplace interesting.

Star Wars was central to my world, but in the same way that water is central to a fish. Every baseball bat was a lightsaber to me. My mom’s vacuum cleaner was R2D2. Even back then, it never made sense to say that Star Wars was my favorite movie — that’s like when Christians say their favorite book is the Bible.

Coincidentally, or maybe not coincidentally at all, it was another of George Lucas’ films that would turn me into a Movie Person (TM). Up until I was a young teenager, the films I loved brought me out of my world. American Graffiti was different — it came to me where I lived and spoke to me about my life. If I can point to a moment where cinema grabbed me and never let go, it was the night I first watched the whole thing in ten-minute YouTube clips on my parents’ computer.

I went into the 50th Anniversary screening this past summer a bit worried that through my grown-up eyes, I would find American Graffiti unworthy of the place it holds in my life. I shouldn’t have worried— it isn’t perfect, but it’s great: deeply affecting, rich in its meaning and symbols, and still the definitive film about the California that I grew up in.

Time/Place

Critics usually frame American Graffiti as a film about a time — the moment in America just before the Vietnam War brought an end to our national adolescence. I’d argue that the film is about the seduction of nostalgia, but its depiction of that particular time is so vivid that it has become known primarily as an object of nostalgia itself. The screening I attended seemed to confirm this — my friends and I were the youngest people in the theater by probably 35 years. The film’s tagline is “Where were you in ‘62?”, and its enduring audience is mostly people who can answer that question.

American Graffiti is about that time, but its place axis operates independently from its time axis. Its world is as recognizable to me, a kid who grew up in Central California in the 2000’s, as it is to my father, who grew up somewhere else (Long Island) in the 1960s.

Modesto, Fresno and the other agricultural hubs along Highway 99 are not the Spingsteen-ian death traps you’ll find in other films about the American heartland (see: Badlands released in the same year). They were and mostly still are fairly well-resourced cities, places with everything you could need to live a regular, middle-class life, especially if you’re lucky enough to be born into one already. The choice to leave the Valley isn’t about survival or necessity — it signals a desire to become something greater.

American Graffiti circles its characters around that place-specific choice and its consequences over the course of one night. Curt (Richard Dreyfus) and Steven (Ron Howard) are on the eve of their departure for college “back east”. Steven is ready to “get out of this turkey town”, but Curt is balking. He can’t name his hesitancy, sheepishly grinning when pressed by Steven about it. It’s a pull of backwards inertia that speaks an appealing truth: if he stops moving, life will stop challenging him.

Some have already made the choice to stay, and it looks irreversible. Local street racing king John Milner is five or so years out of high school but still bumming around with his younger friends, waiting for the next challenger to roll into town.

Where Steven can’t wait for time to move him forward and Curt has his hand over the pause button, Milner’s relationship to the passage of time borders on phobic. His nightlong adventure involves being stuck driving around with the personification of his fear: fourteen-year-old Carol (Mackenzie Phillips) the youth that exposes his age.

When Milner is pulled over by a cop, we learn that it’s his birthday — a milestone that he isn’t able to acknowledge, let alone celebrate. His adolescence in this virtually problem-free town is too strong of a drug to quit.

“I’m staying here, having fun, as usual”

American Graffiti frames nostalgia as a seductive force, one that Curt is on the precipice of succumbing to the way Milner already has. While en route to attend one final high school sock hop, Curt encounters the movie’s most enduring and powerful symbol: a young woman (Suzanne Sommers) driving a white Thunderbird at a stop light.

She’s exactly what Curt is subconsciously looking for — a reason to stay. In his search for her, Curt encounters versions of who he could become if he chooses not to get on the plane the next day.

While roaming the empty halls of the high school, he bumps into an old teacher, Mr. Wolfe, who himself returned home after just one semester at an East Coast college.

“Why’d you come back?”

“I decided I wasn’t the competitive type.”

Life is easier as a medium-sized fish in a Modesto-sized pond. Mr. Wolfe appears to be at peace with his decision. He also appears to be sleeping with a high school student.

When Curt’s search leads him out into the streets, he accidentally sits on a car belonging to a member of The Pharaohs, and is non-optionally invited to ride along on some of their minor criminal activities.

The Pharaohs enlist Curt to help them steal from The Elks Lodge, an extremely boring quasi-masonic club of old men who have recently awarded Curt a scholarship. Both the Pharaohs and the Elks are confident that Curt could find a worthy place in their membership.

Either way, the Modesto version of the future is looking kind of grim. But Curt again focuses in on the idea of an old home made new — that the girl in the T-bird could still want him. A last-ditch attempt to contact her leads him to seek out Wolfman Jack, the Valley’s god of music.

Sound/Nostalgia

American Graffiti has a fully diegetic soundtrack, meaning all the music heard in the film is also heard by the characters. And with the exception of the live band at the high school dance, the music comes from the radio, spun by DJ Wolfman Jack (played by the real guy, neé Robert Weston Smith). American Graffiti’s set of carefully chosen pop songs is a huge part of the film’s nostalgic power, but they’re not just accurate period pulls — the songs drive the emotional content.

Wolfman Jack is an omnipresent character, influencing the story over the air waves, and linking the characters together when they’re separated spatially. This is why Kurt needs to find him — he’s the only person who can connect him to every other person in the Valley, including the girl in the T-bird.

“The Wolfman is everywhere”

The film’s opener on Rock Around the Clock is iconic, but an early needle drop of Del Shannon’s Runaway signals the film’s most important thematic content.

And as I still walk on I think of / the things we’ve done together

While our hearts were young

Nostalgia and music are tightly linked — we imprint on the sounds in the air when we’re young. Songs become time capsules that we fill with the heightened emotions of a particular era of our lives.

I’m lucky that I’ve been able find new soundtracks for every stage of my life — not everyone does. Milner’s nostalgia-induced regressiveness is evident in his rejection of music that’s different from what he loved a few years prior as a teenager — he shuts off the radio when he hears newfangled “surfin’ shit”.

“Rock and roll’s been going downhill ever since Buddy Holly died”

The Skyliner’s Since I Don’t Have You is the emotional centerpiece, hitting at the end of the night when the characters are coming to grips with what they might be losing in the morning.

I don’t have plans and schemes

And I don’t have hopes and dreams

I don’t have anything

Since I don’t have you

It’s fitting that the album cover for the record features The Skyliners posed on an airport tarmac — where the characters’ final choices will be made.

Music is only one half of American Graffiti’s cultural equation — it’s also arguably one of the most important car movies ever made.

Machine/Art

America’s cultural link between cars and freedom is on one level pretty obvious: suburbia makes it impossible to go anywhere or do anything without one. The car is necessary for a basic level of human mobility, let alone as a means of escape.

I don’t think that’s the whole story of Americans and their cars, though. Take a look at the initial confrontation between Milner and his street racing rival, a diabolically cool Harrison Ford in his first-ever film role as Bob Falfa.

Yes, these guys are going to race, but their jabs here are concerned with aesthetics.

“What’s that supposed to be, sort of a cross between piss yellow and puke green, ain’t it?”

“Man, you call that a paint job, but it’s pretty ugly — I bet you have to sneak up on pumps just to get a little air in your tires”

In American Graffiti, the transportive powers of the vehicles are kind of a given. What’s more important is the value of the cars as art objects.

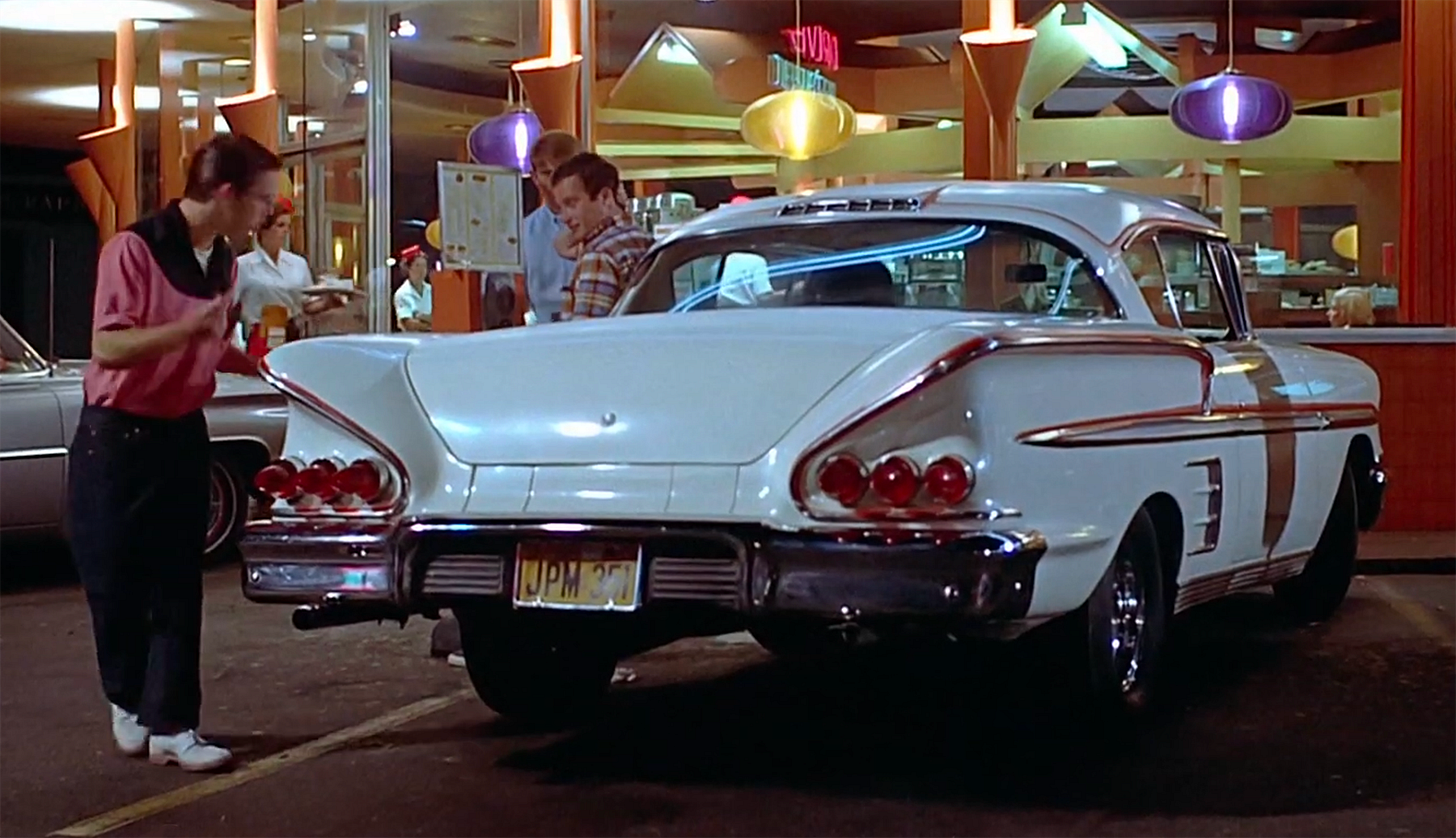

Earlier in the film, Steve gives Terry temporary custody of his 1958 Chevrolet Impala, which understandably causes Terry to lose his mind. He promises to “love and cherish” the vehicle, which has instantly raised his social status in the community.

I think there’s a reason that the aesthetics of car design exploded the same time suburban sprawl did. Automobiles gave suburbanites art objects that they could make their own, share with others, and be proud of. If you’ve ever been to a car show, whether it’s the Concours D’Elegance or local kids parked outside of the Foster Freeze on a Friday night, you know what I’m talking about.

Valley car culture endures 80 years later, in a different form. Now it’s more about sheer size.

We lost something significant when we stopped viewing cars as art, maybe as significant as the loss of vernacular architecture to cookie-cutter tract housing and grotesque McMansions.

I wonder if the chord that American Graffiti strikes with me above all is that in almost every scene, it shows young people engaging with and creating their own forms of culture in a remote environment, which is ultimately the story of my own adolescence.